[Author’s note: What follows is 5,000 words, and I “get” that I’m asking a lot, but it was all I could do to keep it down to that number, and I couldn’t bring myself to split it up. I understand if you can’t take the time to read this all the way through, but I’m pretty sure you’ll be glad you did if you do.]

Dad (Richard Curtis) descended from the first of my line of Poffs, Frederich, who, like many of the Mennonites in the 1700s, was persecuted out of Germany and landed in Philadelphia in 1750. I am unashamedly proud that my people got here a generation before the American Revolution, and my research over the years affirms that my family blood was spilled in both the standing up of this nation, but so, too, was their sweat and tears given to her construction, maintenance, and ongoing armed defense of it. Like so many others in those days, as my family tree spread out, some branches stayed in Pennsylvania while others spread more widely South and West, some settling in West Virginia and some continuing on to Kentucky.

One of five children (that I know of), Dad was born to James and Alma in that ugly stretch of time in American history known as the Great Depression; born three years after it started, the third of five children, the only thing his family knew was abject poverty. They were forced to leave Charleston proper and head out to the more rural regions of Kanawha County, where my grandfather patched together a collection of handyman jobs, many failed attempts at farming and raising chickens, and continuing the family Legacy of alcoholism that had been handed down to him for Generations.

Much of what I know about my father did not come from him; we did not meet each other until I was in my mid-thirties. Most of what I did know came from either my bitter mother, disappointed grandmother, or a shared hatred of him between my brother and myself for a man we were taught to hold in the greatest of, although I would learn much later in life not entirely fairly deserved, disdain.

He had reached out to my brother first, wondering if he would be interested in meeting face-to-face in Boston, where he planned to travel on business. When my brother called me to see how I felt about the idea I was honestly just as conflicted as he was, but agreed I would join him if he decided to accept the offer. As life-changing moments typically do, this one flipped my entire reality upside down and on its ear.

My parents split after I was conceived, but before I was born, so my brother remembered bits and pieces of Dad, and much of that had been tarnished in the years between when he left and that first gathering over dinner at a restaurant in Boston more than three decades later.

My head was in an entirely different place; with nothing to go on outside of what I had heard about him my entire life, trying to take what was sitting across from me at face value, I spent 2 hours being overwhelmed by just how much like him I was, and all the years I spent listening to my family and my teachers telling me they wished I was more like my brother, every goddamn thing I had come to think about myself began to make perfect sense.

He looked more like my brother than me, but his body language and how he expressed himself, carried himself, and told his story made me realize my father and I were the same person. I “get” that a high-dollar shrink would quickly scoff at that, suggesting I was merely projecting, and I might have agreed with them in the immediate days after that first meeting. It’s a funny thing, though, that – by the time he died a few years later – I would come to learn that my first instincts were exactly right. That whole “Nature vs. Nurture” thing? Yeah… Genetics can be a fickle bitch.

By the time we met, my father was on his third marriage to a sweet and wonderful lady – Joann) God Rest her) with whom he had been together for over 20 years. Between them, over several years of written letters and in-person visits, I got the so-called “other side of the story” about my father’s life and all of the things that explained (note that I did not use the word justified) why my father became the man he did, why(and how) he became a lifelong alcoholic, and how it was that he ultimately couldn’t get past is demons no matter how deeply he dug into his bottle.

Around the time of Pearl Harbor, my grandmother Alma had become the first female Post Rider in West Virginia. My grandfather, James (we share middle names), was known around the County as the best house painter money could buy (it was said he could estimate, within a pint, how much paint would be needed for any given job). They started dispatching the kids that were old enough out to work, essentially indentured servitude, wherever work could be found.

My grandfather is said to have been the first Poff to coin the phrase”The Poff Curse” after having decided to try chicken and egg farming. As the story goes, he spent every last penny buying the necessary supplies to build chicken coops and egg boxes… And roosters and laying hens… Along with enough feed scratch to get things started. Where they lived at the time had never had a flood, as in never had a flood where they lived. All the same, once the eggs started coming, the first flood in the history of that area occurred and wiped everything out. What do you think my grandfather decided to do next?

If you are a Poff, at least my branch of the Poff tree, you know exactly what happened next. Liquored up, convincing himself that lightning never strikes twice in the same place, he begged, borrowed, and stole enough to set it up all over again. And, all over again, another flood came and wiped it all out. Again. And for the record? I can assure you the Poff curse lives on.

It wasn’t long after that my grandparents moved the family to Washington, DC. I can’t be sure of the exact date, but I do know that my father attended McKinley Tech High School because that’s where my parents would ultimately meet. In the time between leaving West Virginia and my parents first crossing paths, life was incredibly difficult for my father. He described his mother to me as a mean-spirited and cold woman who showed very little outward affection, really for anyone, but especially for her children, and after the war, they picked up and moved to Washington, DC.

He told me that he was always on his own, hanging around in the alleys, basically living the life of a juvenile delinquent his parents and siblings had convinced him that he was, and he said that there were a number of times when he didn’t come home (sleeping in the alley outside his apartment) and would come home several days later to be treated as if no one noticed he was gone. His two older brothers were either mean to him or ignored him, and he told me that he had once nearly cut off the tip of his finger only to be yelled at by his mother and beaten up by his brother because Alma had made him deal with the mess.

Once he got to high school, he was little more than a feral alley cat; he had very little self-confidence and absolutely no self-esteem. He loved to sing, so he joined the school chorus (he said that’s where all the pretty girls were). Because of his love of Music, he took every band class or engaged in any music-based events available to him and began to think of himself as quite the dancer. He had told me that, never having felt loved or appreciated by a woman before in his life, the positive attention he got in high school from the ladies did wonders for building his confidence and self-esteem. And it was in these days that he met, and fell in love, with my mother who was, using his own words, a damn good singer with an incredible voice.

They graduated high school together in June 1950, just as the Korean War was kicking off. They got married, and he signed on with the Navy and shipped off to war. My brother came three years later, and I was born five years after that… Even as they were already separated and heading toward divorce.

Somewhere in the ’94 time frame, deeply saddened by the slow-motion collapse of my then 15-year marriage (my first), I decided to invite myself to stay with him for a couple of days. I had told him that I desperately needed to understand my past before I did something terribly stupid that would ruin my future. He would tell me, towards the end of that visit, that he wasn’t entirely sure he wanted me to come, suggesting – as I would have were the situation reversed – that there would be no escape route if things got difficult or complicated, or… God forbid… Contentious.

This time with my father, spent over countless pots of coffee and a steady stream of cigarettes, opened my eyes to so many things about my family history that I scarcely know where to begin. As I start this off, listening in my headphones to a song titled “In The Blood” by John Mayer, I smile as I hear these words:

“How much of my father am I destined to become?

Will I dim the lights inside me just to satisfy someone?”

Listening to these words now, I am reminded of what he freely said to me when we first started filling in some holes in each other’s lives; “whatever you think you know about me or have been told is probably mostly true so there’s no point apologizing for the mistakes I’ve made or how my actions affected your life. What I can do is tell you that, given everything I’ve done in my own life, I promise you yours turned out better because I wasn’t a driving force in it.”

Without blinking an eye, I told him that what he was so sure of was absolutely not the case. I reminded him that his absence in my life was made to be the driving force in it, that it was what defined me, and that being angry about it and told to hate him for it was all I had ever been taught. And then I suggested that I would much prefer the truth, even if it were ugly, and we both laughed at how ugly each of us thought some of the pieces of Our Lives had been up to this point; we laughed and settled into the work of laying bare all of our demons and the different ways each of us had gone about the business of trying, and sometimes failing, to overcome them.

It’s worth noting at this juncture that I did not consciously design this presentation of my father’s life and ultimate death to be a collection of snippets bouncing forward and backward in time, but I’m actually glad it turned out this way. Seemingly random vignettes, in seemingly random order, are how I remember my father and how each of us lived our parallel lives.

As we head toward the close of this presentation, readers should appreciate that – just as my father and I developed what would become an incredibly close and deeply personal relationship – we arrived at his final destination having traveled the zig-zag roads of two separate lifetimes jammed into a span of roughly two years. The pace was frantic, my motivation being a desperate need to understand myself and make some sense out of how I got to the place I was in my life as my marriage was falling apart, but he never let on that he already knew he was dying and desperately needed to leave this world, thinking he had done right by at least one of his children.

Much of the first day was spent learning about his family; I learned that his oldest brother had basically washed his hands of the whole family, went on to become a college professor, and had very little to do with the rest of them. He outlived all of them and, for what it’s worth, is one of only three Poff men to make it to 70 (he lived into his 90s), my bar-owning great-grandfather, Robert, eeked his way to 70, my brother sits at 70 and counting, and I have 4 years to go.

Ed only involved himself when someone in the family died. There were so many, or at least it felt that way because the deaths were so close together, that he told me he had spun a little poem about his oldest brother: “Oh dear Lord, here comes my big brother Ed, someone else in the family must be dead.” The second oldest brother died after falling through the ice in Michigan, I believe, and drowning. I’m not sure what year that was, but my grandfather died the year my brother was born, and my father’s youngest brother, Johnny, died in a horrible car accident while my parents were still together.

Dad told me that, after everything he had experienced, having spent his whole life around alcohol, he promised himself he was never going to drink, that he intended to break that cycle in the Poff Legacy, but that it had all gone out the window the minute he stepped on solid ground during his first shore leave when he was in the Navy. Between the time he married my mother and the time he made it back home to her, the man she married no longer existed, and with every glass and every bottle and all the songs, music, lyrics, and bands he had come across, he had turned into someone he couldn’t recognize but couldn’t get away from.

The last straw of any hopes for sobriety was dropped, like a ton of bricks, on his already weakening back and broke him for good one night in a DC bar when he was out with his youngest brother, Johnny. They were drinking together, got into an argument, and my father left him there and headed back home. A couple of hours later, the phone rang off the hook as my mother kept answering but couldn’t wake him up (passed out drunk) to take the call; he would learn the next morning that Johnny had jumped in his car and tried to chase after my father, only to die before getting to him. Dad told me, blaming himself for the rest of his life, that the alcoholism took over control after Johnny died. JoAnn would tell me, after Dad’s death, that Johnny’s death only set in motion the downward spiral but that things got a whole lot worse during the years that came after.

I will never know why, for sure, although it was likely by design, he waited until the second day to tell me that I had two half-brothers and a half-sister who had come after me. He never married their mother (although he died believing she was the one he had always felt he was destined to be with), and two of those children had died. I remember thinking, at that moment, that the oxygen had been completely sucked out of the room. My mind was racing, as pieces of me were trying to do the math on the timing of those children and the timing of when my parents divorced, but I never got the chance to ask; my father was an incredibly intense man and, if you didn’t keep up, paying very close attention to his nuance and innuendo, you were going to fall behind and never recover. He blew right past the whole thing before I could start asking any questions and, instead, immediately moved on to discuss his relationship with their mother and how it was that everything had fallen apart between them. It was JoAnn who gave me the excruciating story after Dad’s death, but we will get to that shortly.

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, my father had become quite proficient with the guitar and drums and fancied himself an up-and-coming songwriter, quite proud of his mad skills at writing lyrics. I know of at least one song he wrote and had copyrighted, which I had heard about but never heard or seen, that he had written (which I wouldn’t know about until many years after his death) to memorialize the pain and sadness he felt for having left my mother, my brother, and me. He spent every possible moment hopping from bar to bar, and Honky Tonk to Honky Tonk, drinking, dancing, and making friends with any talent he could introduce himself to, and even stepped in to sing or play with any of the local bands that came and went on their way toward making it to the “big time.”

He told me that he had hung out and gotten drunk with the likes of then-unknown artists such as Roy Clark, Willie Nelson, and Johnny Cash and had even thrown down with Elvis Presley once. I can’t prove any of that, but I have no reason to believe he bothered telling me the story if it wasn’t true. He said that sometimes he would, as the least drunk of the lot, drive them to their motels after the bar had shut down or go backroading until the sun came up or they passed out in the car on the side of the road somewhere. What he didn’t tell me, but what I would hear from JoAnn much later, was that he would also follow some of these guys off to the next town, and the next town, and any town in between, until he would run out of money and have to head home. These lifestyle choices of his only ever had one possible outcome, and before the seventies arrived, the mother of my half-siblings had kicked him to the curb. But there is something missing from this story, like that 900 lb gorilla in the room, and knowing that he intentionally chose to take it to his grave – no one but Joanne knowing this part of his story – explains why my father spent his whole life running from himself, hiding from his memories and emotions, and why it means so much to me to see to it that it be told.

The oldest child, the daughter, accidentally shot the first son in the head, killing him instantly while playing with a pistol no one ever explained how they had gotten access to. JoAnn told me that his son’s death at the hands of his daughter had driven him to such drunken sadness and self-abuse that he could never get past that same feeling of guilt he had experienced all those years earlier over his brother Johnny; “if only I’d been there…”, “I bought that gun for their mother to protect the family when I was away, this is my fault – this is really me who pulled that trigger,” and so forth. The breakup of the relationship is understandable, and the loss of the child – regardless of the circumstances- is something that is well known to bring even the closest of relationships to an end. Unfortunately, it doesn’t end there.

The daughter struggled with what had happened her whole life, as did the youngest brother, that has survived them, but at some point in her early twenties, she was raped and murdered and died a horrible death. Joann told me that my father sat in the courtroom every day of the trial and wept and that whatever pieces of him that might have been left inside were gone and lost forever after that.

It wasn’t much longer after that time that Dad had been diagnosed with terminal Cirrhosis of the liver and, making him one last vodka straight up in a beer glass on the way to check in to the hospital to die, between groans of pain and anguish he apologized for everything he had put her through and told her he had deserved every bit of what was coming to him and was not afraid to die for it. The funny thing about my father, though, is that the stubborn bastard didn’t die; after a couple of months in the terminal Ward, still upright with moderately returning liver function, they kicked him out and sent him back to her. Now, my father always believed in God, but he was pretty sure God didn’t believe in him, and since God clearly wasn’t done with him just yet, he decided to find his three remaining children and see which of them might be interested in any sort of reconciliation.

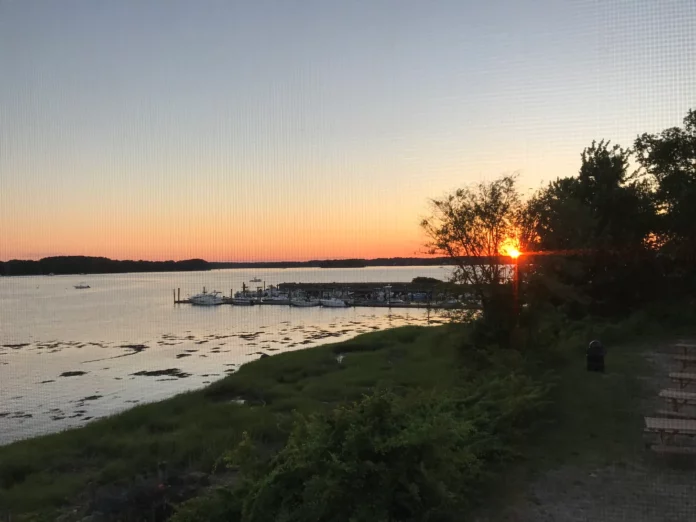

On the last day of my visit, Dad told me he had to go out for a few hours and that I was welcome to hang around at his house or walk the downtown streets of Chesapeake City (he had lived there for years with JoAnn) but had been long separated from her, and that there were some pretty cool shops and even a place to park where I could look out over the water and watch the big freighters and sailboats moving about. He was always an ocean guy, as I have always been an ocean guy, but I had already long given up trying to keep count of all the things the two of us had in common despite having never seen each other in the three-and-a-half decades before our reconciliation had begun.

I didn’t ask where he was going, and he didn’t offer, and I chuckled a little bit as I sat at the waterfront watching the boats, wondering if he was going to disappear like he had told me he spent his whole life doing. It was only after he died that I found out he did a lot of volunteer work with veterans as well as taking people to and from AA meetings; he had long ago quit drinking because of his liver issues, and he didn’t sponsor anyone, but – understanding the disease as well as he did – he offered comfort and support to anyone that genuinely needed it, and that’s where he had gone when he left me that day.

I went back home, initiated the separation in my marriage, and moved into what was the most favored place I have ever lived: a small cabin at the edge of a pond with no running water and only an outhouse. My bathtub was the pond, which was a few naked but for a towel wrapped around you steps away, a bar of Ivory soap in hand, and I loved every minute of living there. Cell phones weren’t a thing back then, and I spent the days between child visitation and talking to my father on the phone. During that stretch of time in my life, the two of us became best friends, talking about anything and everything under the sun and never running out of things to talk about.

I eventually tried to reconcile with my first wife, and although the attempt ultimately failed, there had been a lapse in my interaction with my father for a brief time. He had put together this Grand idea that since he hadn’t died when he should have, he might as well do something productive with whatever life he had left. Sound familiar? He had been pitching the idea of hiking the entire Appalachian Trail – with financial support from sponsors – and that he would write a book about the experience. It was actually a pretty decent idea, except he never found anyone willing to sponsor him. And, like the failed second attempt at chicken and egg farming by his father before him, he headed to Florida to find day labor since the Maryland weather was working its way back toward winter in late ’96.

I didn’t hear from him or JoAnn through Christmas and New Year’s, but I got a frantic phone call from JoAnn in mid-January of ’97. My father had shown up at her doorstep, deathly ill, and she did not know what to do. A couple of days before she called me, she had called 911 because he was in really bad shape, but when they arrived, he had refused to let them render aid or transport him to the emergency room. She had begged and pleaded with him, and he had told her that all he needed was a little rest and that he would be fine. He wasn’t fine; he was uncontrollably vomiting, unable to control his bladder or his bowels, and spent 90% of his time either unconscious or moaning in great pain and agony. She told me that she had offered to call me on his behalf, but he never answered her, and she begged me to come help both of them find a way to ease his suffering.

I got to them as soon as I could, late the next evening, and sat with JoAnn for a while, getting caught up on what the hell had happened. She told me he had made it to Florida but had gotten terribly sick not long after and had made his way back North to Maryland. He had apparently given up his apartment when he headed south and had nowhere else to go, which is why he landed at her front doorstep. She told me that he looked like walking death when she opened the door and that I should steel myself for what I was going to see when I went into his room. Once I got in there, though, what looked back at me was terribly worse than she had prepared me for; he was completely yellow, literally Skin and Bones, and what few words he could muster were more or less complete gibberish that didn’t make any sense. I convinced him to lay back down and try to get some rest, and then he was unconscious.

I stayed in the room with him overnight, sleeping – sort of – in a chair at the foot of his bed. It’s a night I will never forget, but in the hours I spent watching him slowly die, wasting away to nothing, he couldn’t have been much over a hundred pounds at that point; I knew there was only one thing I could do about it.

The following morning, I went out to sit with JoAnn over coffee and talk about whatever end-of-life plans the two of them had ever worked out for him when it was his time. She said there really weren’t any, that nothing had ever been written down, and that – as I had seen for myself – he wouldn’t be able to remember any of it or communicate any of it now. I told her I intended to scoop him out of his bed and carry him to my car, drive him to the hospital emergency room whether he wanted it or not, and have them assess his condition and ultimate prognosis. She agreed, followed behind me in her own car, and they came out with a stretcher to wheel him inside.

After what seemed like an eternity, although it was probably no more than an hour, the doctor greeted us in the waiting room. We were corralled into a small office to have a little privacy to discuss my father’s situation. We were told that he was in complete liver failure, that initial tests showed he had end-stage liver cancer, and that he only had hours, or maybe a couple of days, before he would die. JoAnn wept, as much for my father as for knowing her struggles with him were, thank God, finally coming to an end, and asked me what I thought she should do.

The doctor asked us about the end-of-life plans, and she gave him the same answer she had given me.

Because they had never been officially divorced and because he could not communicate – not sensibly, at least- the doctor said she could assume guardianship on his behalf so that she might give final orders for his treatment. She said she didn’t want that job but would take it so long as she and I agreed on what would be best for him.

As the doctor laid out his care options, telling us they could begin chemotherapy and radiation in an attempt to slow down the progression of the cancer, he explained to us that only a liver transplant offered any chance of a longer-term survival and that he could die during the chemo or before a donor could be found. It wasn’t a hard call to make. Both of us, each in our own unique ways, knew he would not want any part of any of that, so she signed off on making him comfortable and letting him go on his own terms… Both of us agreed that it was what he would have wanted.

Once he was admitted and taken to his room, we went in to see him for what would be the last time either of us saw him alive. JoAnn lasted about 5 minutes before having to excuse herself from the room (one last kiss on his unconscious forehead) and headed out the door, telling me she would meet me back at the house.

When she had gone, I sat down on his bed and started talking to him knowing full well he might not have heard a word I said. I told him he didn’t have much time left, that he had a great room with a view over the water, that he looked like shit, and that his Hospital Johnny was not a good look for him.

I told him I would miss him, that even though he would disagree, I thought he was headed for a better place, and that he was finally going to find some peace. I leaned way in, as I rubbed his hair and his forehead, and told him that I loved him. It was strange, saying that out loud, because I never had before, and as I realized that… Even though he never opened his eyes… he somehow summoned the strength to say”Me too, “and just like that, we would part ways with the closure each of us had been looking for, but neither thought we’d ever get.